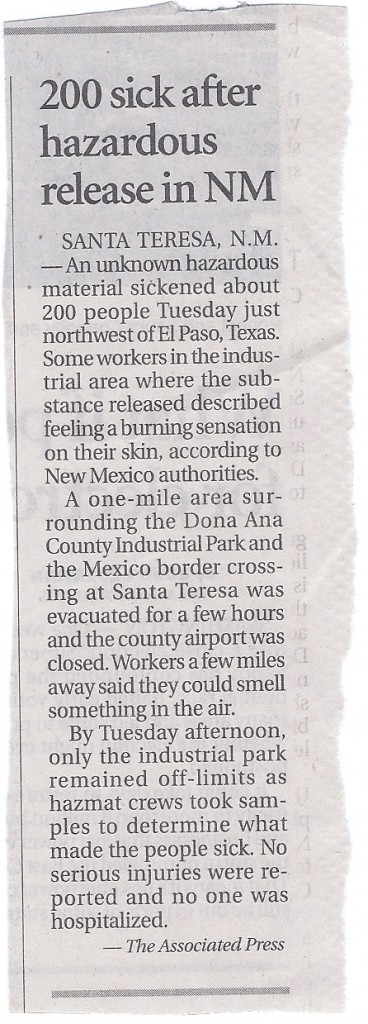

You already knew it. There is a lot to do in industrial hygiene. At times this occupation feels like a safety middleman trying to keep people out of trouble. Occasionally I’m rewarded with really helping someone. In the United States, there is still a lot of occupational hygiene issues and concerns. Overseas, particularly in developing countries, there is even more.

It is hard to obtain accurate exposure data, or illness rates, from these underdeveloped countries. (How does a village of 1,000 people in Kenya report that they’ve had lead exposure to battery recycling?) How these exposures are brought to light is by either a massive death (# of people, quickly) or, someone with a camera able to actually photograph the pollution. As we know, what it looks like doesn’t necessarily correlate with hazardous levels of exposure. But, in some cases, it’s pretty obvious.

I ran across this photo story on pollution (The Guardian, UK).  They estimate 125 million people are exposed to industrial pollutants (generic term, I know). This makes occupational related exposures a health risk as big as TB and Malaria! The article is based upon a report from the Blacksmith Institute which included this map of the worst pollution with associated disease.

They estimate 125 million people are exposed to industrial pollutants (generic term, I know). This makes occupational related exposures a health risk as big as TB and Malaria! The article is based upon a report from the Blacksmith Institute which included this map of the worst pollution with associated disease.

How does this apply to construction? The worst offenders are lead (Pb) (and other metals), and asbestos.

What can you do? Here’s their recommendation, from the report (p50):

Developing countries need the support of the international community

to design and implement clean up efforts, improve pollution control technologies, and provide educational

trainings to industry workers and the surrounding community

Another NPR article about lead poisoning can be found here.