Entries tagged with “safety”.

Did you find what you wanted?

Thu 6 Sep 2012

Posted by admin under Admin Controls, Air Monitoring, Engineering Controls, Exposure, Federal OSHA, GHS, Hazard Communication, industrial hygienist, Management, MSDS, OSHA, PEL (Perm Exp Limit), Safety Policies, Training

Comments Off on When do you resample?

After performing an industrial hygiene survey (air monitoring), have you considered when you should resample? Here are some considerations that might help you in determining when.

- Are there specific rules that state when you must resample? For example, the construction lead standard (1926.62) states that you must resample yearly (or actually, that you can only use relevant results for one year).

- Has the process changedsince the last time you sampled? This one is hard to determine. Lot of things can change air monitoring results, here’s a “starter list” of things that can change a process.

- Different employee?

- Time of year? Summer versus winter? (closed up/open and humidity)

- Is a new tool in place?

- Has the ventilation changed?

- Have new controls been put in place? (administrative, systems operations)

- Has the product changed? Check the safety data sheet (aka MSDS).

- Are more (or less) employees exposed to this hazard? This might change some assumptions you have made about your risk.?

If you have air sampling performed, make sure you have a written report of your findings. Laboratory results without an explanation of how they sampled, where, # of employees, process description, PPE used, safety data sheets, etc….is worthless. You may remember is well enough, but OSHA will have a hard time believing that it is a similar exposure the next time you do the “exact same thing”.

Having this report and sharing it with the employees will fulfill (part of) the hazard communication standard requirement to employees.

Tags: air monitoring, air sampling, exposure monitoring, GHS, industrial hygiene, MSDS, OEL, OELs, OSHA, report, safety

Thu 30 Aug 2012

As common as it sounds, falls in construction are still the #1 killer.

Go to www.osha.gov/stopfalls

This site has good information, reminders, training, and resources.

Tags: construction, fall protection, falls, height, industrial hygiene, lanyard, OSHA, roof, roofing, safety, tie off, yoyo

Tue 28 Aug 2012

Posted by admin under Asbestos, Federal OSHA, Hazard Communication, Management, OSHA, Training, Uncategorized

Comments Off on What makes it “hazardous”?

I love the show, “Dirty Jobs” with Mike Rowe. I find it fascinating what people are willing to do for work. Many of the jobs on the show have a true element of danger. Either a pinch point, an animal bite/kick, struck-by, heat/cold extreme, confined space, etc.

Did you ever consider what makes something hazardous?

My “deep thought for today” (thanks Jack Handy) is that education and training can make a job less hazardous. If you know how to do it right, and you know the risk, it doesn’t seem as dangerous anymore. The risk is there, but you know how to handle it, so the “hazard” seems to fade. This week I’ve given two separate asbestos classes to two different employers. At the beginning the employees were genuinely concerned about the hazards. By the end, they looked a lot more comfortable about upcoming project.

Is it any surprise that the HazCom standard is the most OSHA cited rule year over year?

So, keep up the training! Educate the employees on the dangers.

Thu 16 Aug 2012

Posted by admin under Air Monitoring, Cadmium, Concrete, Drywall, Dust, Exposure, Hexavalent chromium, industrial hygienist, Lead, Management, Mold, Silica, TWA, Welding

1 Comment

When performing air monitoring it can be useful to take multiple samples on the same individual throughout the day. Here are some reasons to change out the filters:

- build up of dust on filter – can cause overloading

- break-out the exposure data. Morning versus afternoon, or by job tasks, or the physical area the employee is working in, controls vs. no-controls, etc.

- if you question the employees motives. If you think the employee might skew the results, multiple samples might give you better control- or at least tell you if one is way-out-of-line.

Once you have your data results, how do you combine them?

If you’re taking particulate (dust, lead, cadmium, silica, etc) and you have the concentrations (from the lab) here is what to do.

- note the time (in minutes!) and the concentration results (mg/m3, ug/m3, etc) for each sample

- multiply the time and concentration for each – then add each number together

- finally, divide the above number by the total number of minutes sampled. This is your time weighted average (TWA).

Simple?! Yes. …And it’s really easy to make a mistake too. Check your math, and then eyeball the results and see if they make sense logically.

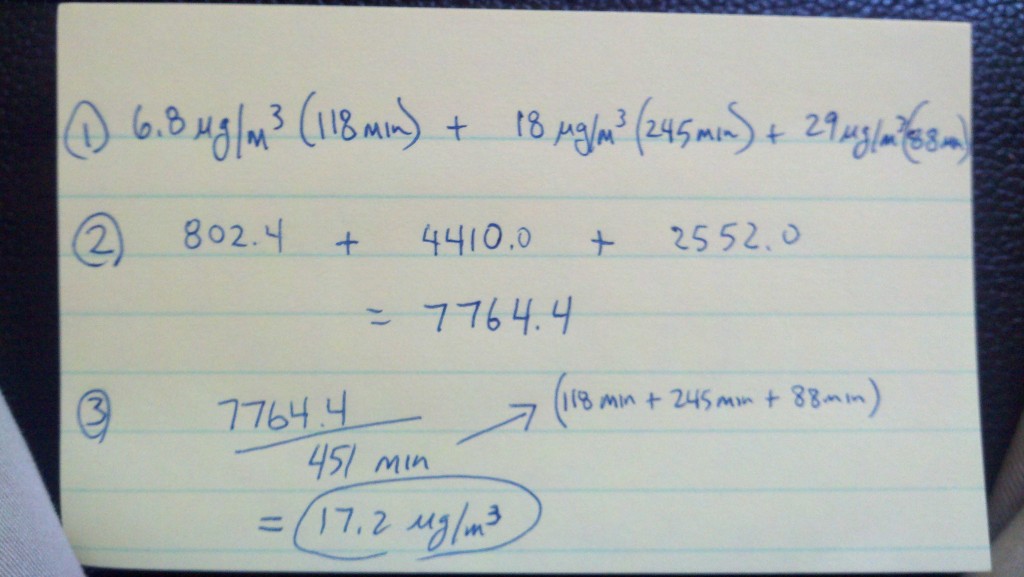

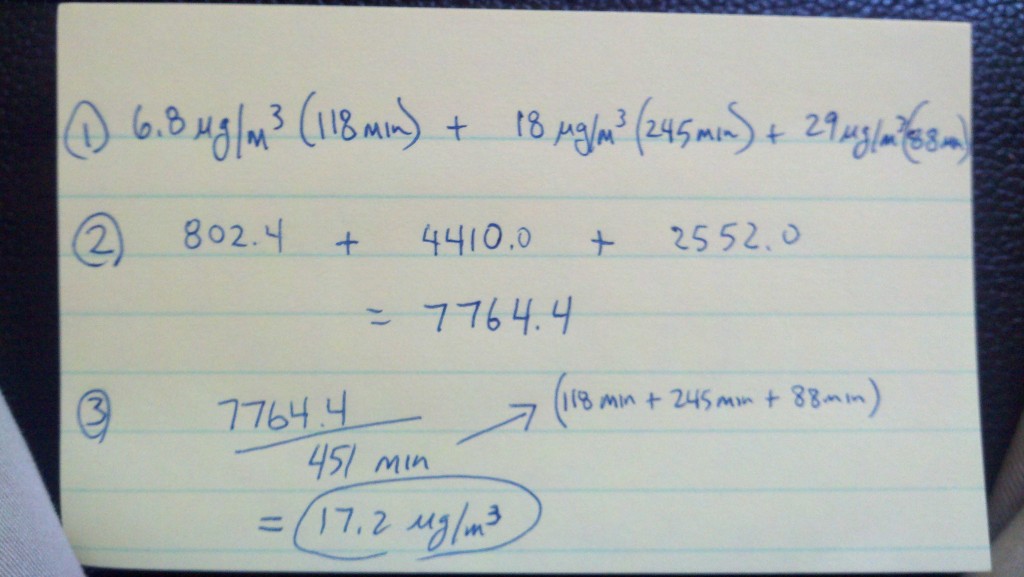

Here’s an example:

Andrew took three samples during one shift while Shelley was rivet busting through leaded paint. The first sample (118 minutes) was reported as 6.8 ug/m3 of lead, the second was for 245 minutes and had a concentration of 18 ug/m3. The last sample was taken for 88 minutes and was reported a level of 29 ug/m3. The overall results is 17.2 ug/m3 for the total time sampled. (Side: if you sampled for their entire exposure, and they worked longer hours, you could add those hours (assuming zero exposure) into the final time-in step three)

See the math below:

Wed 25 Jul 2012

As I have said in an earlier post, some OSHA, EPA, and MSHA rules are a good fit. They blend well with health research, scientific technology, good practices, and a low-cost-of-compliance for employers. Other rules are just bad. They are  totally out of date, not protective enough, or just not feasible/practical. Here’s my plug for a good safety manager/industrial hygienist – A good one will know which rules/guidelines to follow.

The New York Times (July 19, 2012, Cara Buckley) recently wrote an article on the US noise standards which are not protective enough for employees. In construction we also have three additional problems.

- hearing loss is expected (or at least assumed in certain fields – carpenters, sheetmetal, ironworkers, etc.) and,

- work shifts are usually over 8-hours. Noise exposure is usually calculated on an 8-hour time weighted average. During the busy months, an 8-hour work day is rare. It’s at least 10, maybe 12-14 hours. This doesn’t allow your ears to “rest” between shifts. For more information on extended work shifts go here.

- extracurricular activities contribute to overall hearing loss – my point is that most construction workers don’t sit at home at the end of their shift. Almost everyone I know in construction is involved in one of these activities: hunting, shooting, motorcycles, water sports, yard work, cars, wood working/cutting, concerts, music, etc. Each of these activities contribute to their overall hearing loss, and again, doesn’t allow your ears to “rest”.

…which reminds me that I need to keep a set of ear plugs in my motorcycle jacket.

Tags: ACGIH, dBA, dosimeters, EPA, hearing loss, IH, noise, OSHA, safety, sound, sound level, standards, TWA

Fri 20 Jul 2012

Are you measuring for zero accidents? Is this even possible? I agree it is a worthy goal. But, if you are presenting this to management, can you actually achieve it?

There is plenty of discussion around this issue. Maybe a better goal is something harder to measure, but more successful/beneficial in the long term. What about measuring one of these? (or a combination)

- response time from complaint to resolution (from employees)

- number of requests for safety related issues

- satisfaction of safety by workers (rate 1-10)

- safety committee interest & interaction

- decrease in airborne exposure levels year over year

- keeping track of engineering/administrative controls put in place per year

My 2 cents.

Wed 18 Jul 2012

Posted by admin under Air Monitoring, Asbestos, Building Survey, Hazard Communication, Management

Comments Off on What if you’ve had asbestos exposure?

Occasionally (actually, far too often), I hear from a subcontractor who was told by the General Contractor (or owner) there is no asbestos onsite. Then, after they have been working for a month they find out it actually IS asbestos, and they were disturbing it. What do you do?

Occasionally (actually, far too often), I hear from a subcontractor who was told by the General Contractor (or owner) there is no asbestos onsite. Then, after they have been working for a month they find out it actually IS asbestos, and they were disturbing it. What do you do?

The first thing to do is stop work. Do not try to clean it up. Call an abatement contractor. They will identify the asbestos onsite, clean it up, and provide an airborne clearance test.

Next, you will need to provide awareness training (or better, let the abatement company provide it). Ideally this will occur on the day you start back working. Train everyone onsite about asbestos.

Finally, you (as the safety manager), need to identify and characterize the exposure to the employees. It should probably be a formal letter written to the owner, general contractor and employees.

Here are some tips on writing the letter:

- include employee names, work hours, type of work, PPE worn, and locations they were working

- describe the asbestos. Amount found, locations, type, estimated amount disturbed.

- describe remedy process and steps taken. Names of GC, owner, abatement company, airborne levels found. Who was trained afterwards.

- describe how things will change in the future. Here’s a tip: Â any building before 1985 WILL have a building survey performed for asbestos….in writing.

Really, one exposure to asbestos is probably* not enough to contract a disease (asbestosis, or mesothelioma). It will take 15-30 years for symptoms to appear. But, it might be worth the “goodwill” to send affected employees into a occupational health doctor for a check up. The physician will reassure the employee and may provide some comfort.

*asbestos is a carcinogen. Greater exposure = greater chance of cancer. no amount is safe.

Mon 16 Jul 2012

Posted by admin under fit testing, Respirators, Safety Programs, Training

Comments Off on Fit Testing – tips and suggestions

There are two types of fit testing, 1. quantitative and, 2. qualitative. For quantitative fit testing you’ll need a machine (ex. Portacount), Â a respirator that will protect more than 50x the limits (>full face). Â I will not cover this type of fit testing in this post, but it is very similar.

For qualitative fit testing you will need:

A medical clearance (not needed if you are wearing a paper dust mask) for each employee wearing a respirator.

Respirator w/P-100 filters (1/2 face respirator or more protective), aka HEPA filters, purple in color.

fit test kit -your choices are: saccharine, irritant smoke, Bitrex, or isoamyl acetate-bananas. Buy it online, or at your local safety supplier. Look at their instructions.

My preference is to use irritant smoke. The reasons are;

- Â if they cough, it means they smelled it.

- it doesn’t require a containment to be built to perform the fit testing.

The employee must be clean shaven around where the mask touches the face. Â I allow “short” goaties where the facial hair does not touch the mask. The fit test procedures are easy to follow and found inside the kit. There are 8-steps, do each one for about 1 minute each.

As you fill out each individual’s form, make sure you include:

- if the employee is clean shaven

- what type of respirator is being worn (size, brand, model)

- what type of filters are being worn

- what type of fit test kit you used

While you have the employee captive, you might as well give them some training. Here are some questions and/or points to note.

- did you train them on positive & negative fit checks?

- why are they wearing a respirator?

- what are the limitations of their respirator?

- how will they store the respirator?

- how will they sanitize it?

- will they share their respirator?

Finally, sign and date the form. It expires one year from this date. Simple? yes. Â Easy to forget something? yes.

Tags: fit check, fit test, fit testing, IH, industrial hygiene, qualitative, quantitative, respirator, respirators, safety, train the trainer

Thu 12 Jul 2012

Living in the NW, stucco is not as prevalent, compared to other areas of the US, as a building material. I finally got the opportunity to perform air monitoring for silica during stucco crack repair. From what the contractor explained, only the top layer of stucco (1/8 inch) is removed. He claimed the top layer is mostly an acrylic. The employee was wearing a 1/2 face tight fitting respirator with P100 (HEPA) cartridges. In addition, engineering controls were used. Â  The contractor had a grinder with a shroud and vacuum to remove the dust. This would not be considered a worse-case sampling scenario. From conversations with the plasterer-employees onsite, grinding is usually “VERY dusty”.

The contractor had a grinder with a shroud and vacuum to remove the dust. This would not be considered a worse-case sampling scenario. From conversations with the plasterer-employees onsite, grinding is usually “VERY dusty”.

Sampling performed only for the duration of the grinding (3 hours). Conclusion?: We did not find any detectable levels of silica or respirable dust.

Please don’t use this sampling as the only information on how to proceed for your project. However, here are my observations:

- If acrylic material is the top 1/4 inch, you may not impact silica (or have any airborne).

- Airborne dust was very well controlled by grinder with shroud & vacuum (see pic below).

- Assume you will have dust until you can observe (or prove) otherwise. Wear a respirator.

- Perception is huge. If there is a big dust cloud coming from your grinder—even if there’s no silica… the observers don’t know the difference, and, well,…you know the story.

Mon 9 Jul 2012

Posted by admin under Asbestos, Lead, Management, Silica, Training

Comments Off on Construction Training Idea – add Silica

I was asked to perform asbestos training…and, “…maybe talk a little on lead”. However, I knew the employees needed to hear something totally different.

The firm requesting the training was a large excavation company that does a lot of road work. The training was at their bi monthly company wide meeting . I was given one hour.

So, my idea: Give them a quick overview of asbestos and lead, and then talk to them about silica. I called the training, “IH Health Topics in Construction”. And, as suspected, the questions that were posed all dealt with either: 1. “in my home I have…” or 2. silica and how to protect themselves.

I have made it my personal aim to talk about silica to as many employees as I can. I throw it into any training (even if I have just 5 minutes). Chances are, these guys WILL have overexposure to silica. Â The owner did not mind since I told him we were going to talk about a few different kinds of health issues in construction.

My suggestion: see if you can work Silica into your conversations and trainings.

Tags: construction, cristobalite, excavation, IH, quartz, safety, silica, silicosis, train, trained, training