Thu 16 Aug 2012

Combining multiple exposure data?

Posted by admin under Air Monitoring, Cadmium, Concrete, Drywall, Dust, Exposure, Hexavalent chromium, industrial hygienist, Lead, Management, Mold, Silica, TWA, Welding

1 Comment

When performing air monitoring it can be useful to take multiple samples on the same individual throughout the day. Here are some reasons to change out the filters:

- build up of dust on filter – can cause overloading

- break-out the exposure data. Morning versus afternoon, or by job tasks, or the physical area the employee is working in, controls vs. no-controls, etc.

- if you question the employees motives. If you think the employee might skew the results, multiple samples might give you better control- or at least tell you if one is way-out-of-line.

Once you have your data results, how do you combine them?

If you’re taking particulate (dust, lead, cadmium, silica, etc) and you have the concentrations (from the lab) here is what to do.

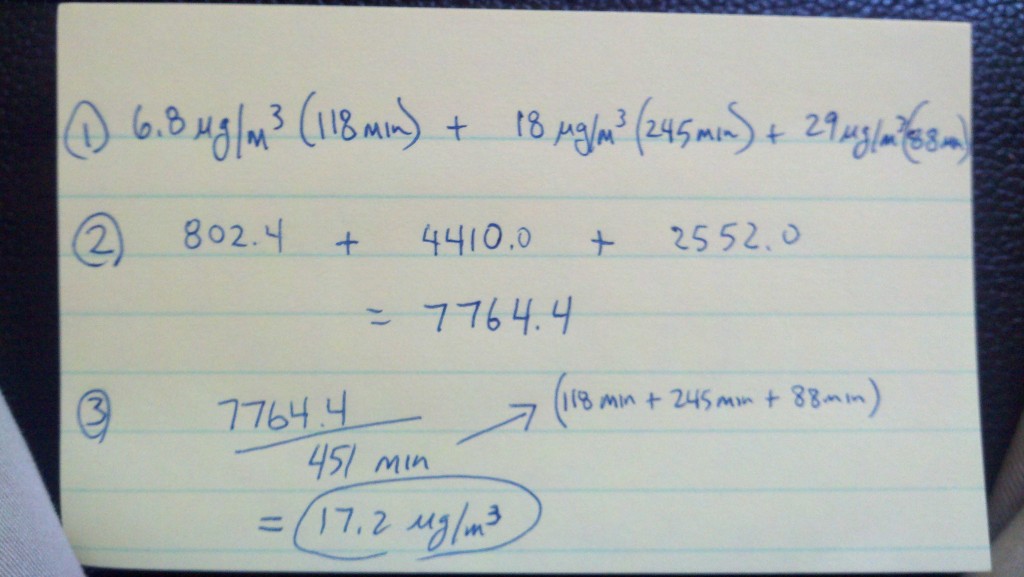

- note the time (in minutes!) and the concentration results (mg/m3, ug/m3, etc) for each sample

- multiply the time and concentration for each – then add each number together

- finally, divide the above number by the total number of minutes sampled. This is your time weighted average (TWA).

Simple?! Yes. …And it’s really easy to make a mistake too. Check your math, and then eyeball the results and see if they make sense logically.

Here’s an example:

Andrew took three samples during one shift while Shelley was rivet busting through leaded paint. The first sample (118 minutes) was reported as 6.8 ug/m3 of lead, the second was for 245 minutes and had a concentration of 18 ug/m3. The last sample was taken for 88 minutes and was reported a level of 29 ug/m3. The overall results is 17.2 ug/m3 for the total time sampled. (Side: if you sampled for their entire exposure, and they worked longer hours, you could add those hours (assuming zero exposure) into the final time-in step three)

See the math below: