Fri 12 Oct 2012

Air Monitoring – Multiple samples throughout the day

Posted by admin under ACGIH, Air Monitoring, Chemical Exposure, Exposure, industrial hygienist, Management, PEL (Perm Exp Limit), TWA

Comments Off on Air Monitoring – Multiple samples throughout the day

When measuring by air sampling for a job task, or an employee’s personal exposure, how many samples should you take?

Sometimes it is easier to place one filter cassette (or media) on the employee for the duration of their day.  At the end of the shift, you collect your equipment, mail it to the lab, and they spit out a 8-hour time weighted average (8-hour TWA). This is simple and easy to understand.

However, if you have the time and resources, it is usually beneficial to obtain multiple samples throughout the day. Taking multiple samples allow you to:

- obtain peaks, lows, and anomalies.

- look at: set up & clean up activities (separate from daily tasks)

- measure multiple employees doing the same task (to better capture the job task)

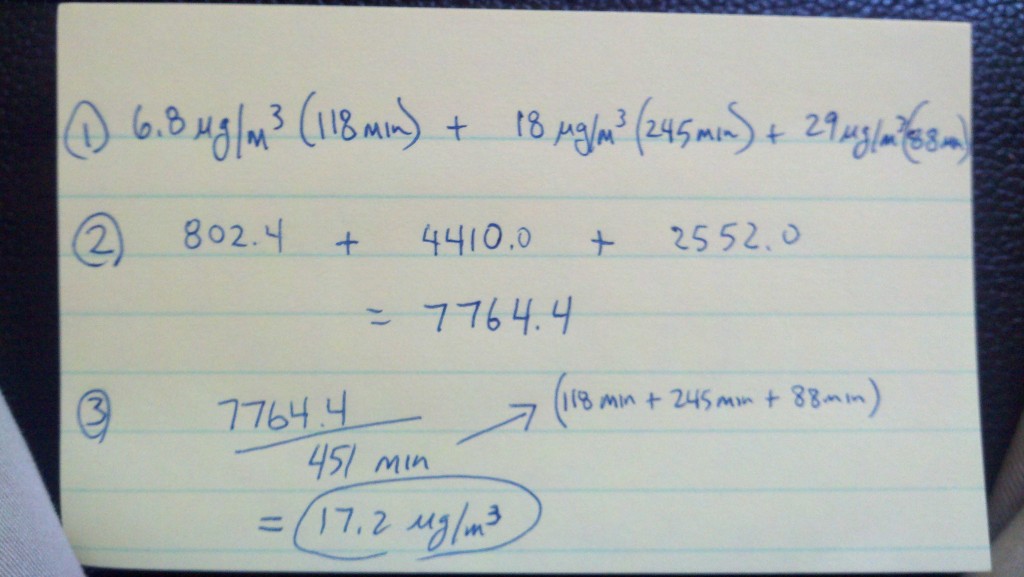

- calculate your own time weighted average

- capture short term exposure levels (STELs), or excursion limits *

- choose appropriate PPE for short duration tasks

- determine if employees are “falsifying” the data (skewing the data high or low)

- reduce filter overloading (in some cases)

There are some reasons NOT to obtain multiple samples:

- collection limit constraints (sometimes the method of sampling does not allow for this type of multiple sampling)

- it can be costly

- it is very time consuming (and nearly impossible, if you have multiple pumps on multiple employees throughout the site)

- difficulty interpreting the data (the math, the inferences, etc)

If you are hiring an industrial hygienist to perform air monitoring, ask about multiple samples. It might be slightly more expensive, but the information and data might be worth the cost.

*ACGIH recommends that if the compound does not have a STEL, all airborne levels should not exceed 3x the 8-hour TWA as an excursion limit.